Why Are the Most Common Verbs Irregular?

Back when I was learning Portuguese, I often found myself wondering something that most language-learners probably wonder at some point: most verbs seem to follow some pattern, but some verbs have some really weird verb conjugations–what’s up with that? What’s more, why is it that the most common verbs are usually the ones with the most weird conjugations? It’s like someone purposefully designed this language to be hard to learn!

As it turns out, somebody didn’t design it to be that way. Rather, natural processes designed it so; processes that have been playing out over thousands of years.

A Day in the Life of a Language Learner

Let’s learn some verb conjugations in Portuguese, yay! This will be fun!

andar (to walk):

| Portuguese | English | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person present | eu ando | I walk |

| 3rd person present | ela anda | she walks |

| 1st person plural present | nós andamos | we walk |

| 3rd person plural present | eles andam | they walk |

Nice! These verb conjugations follow a clear pattern; that’ll be easy to remember.

ser (to be):

| Portuguese | English | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person present | eu sou | I am |

| 3rd person present | ela é | she is |

| 1st person plural present | nós somos | we are |

| 3rd person plural present | eles são | they are |

Ugh! These are some weird ones, how will I remember them? And why does “to be” have to be the verb with all the weird conjugations? Couldn’t a less frequent, less useful verb have the weird conjugations?

Ain’t Nothing Wrong with Being Weird

What I’m calling a “weird” verb conjugation here is actually referred to as “irregular” in language and language learning. In any language, there are regular rules for verb conjugation that the vast majority of verbs follow (e.g. “andar” follows them all). Any verb conjugation that does not adhere to these rules (such as those of “ser”) is called “irregular”.

In the table below, irregular verb conjugations are bolded, and regular verb conjugations are unbolded:

| regular rules | andar (to walk) | chegar (to arrive) | dar (to give) | ser (to be) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person present | -o | eu ando (I walk) | eu chego (I arrive) | eu dou (I give) | eu sou (I am) |

| 3rd person present | -a | ela anda (she walks) | ela chega (she arrives) | ela dá (she gives) | ela é (she is) |

| 1st person plural present | -amos | nós andamos (we walk) | nós chegamos (we arrive) | nós damos (we give) | nós somos (we are) |

| 3rd person plural present | -am | eles andam (I walk) | eles chegam (they arrive) | eles dão (they give) | eles são (they are) |

Where do Irregular Verbs Come from?

You might notice in the table above that the verbs are ordered from left to right, by both increasing frequency-of-usage and number of irregular conjugations (in Portuguese, like in English, “to give” and “to be” are two of the most commonly used, most irregular verbs). This correlation between frequency-of-usage and number of irregular conjugations is generally the rule, regardless of the language. So, why is this the case?

I started researching this question, and came across an interesting hypothesis by a linguist /u/bohnicz in a thread on the linguistics subreddit:

At least for [Indo-European] languages, the verbs meaning to be (usually) are the most irregular verbs in the entire language, with a so-called suppletive paradigm consisting of three or more different roots.

Just take a look at the Old High German forms of sīn ‘to be’: bim ~ bin : bist : ist ; birum ~ birun : birut : sind (Indicative) sī : sīst : sī ; sīn : sīt : sīn (Subjunctive) This paradigm already contains words formed from three different roots, and we havn’t looked at the past tense and conditional mood yet…

Irregular verbs tend to be VERY old and highly frequent in use - being highly frequent is in fact what keeps them from becoming “regular” verbs.

Use It or Lose It

So, it’s less about where the irregular verbs come from, and more about where the regular verbs come from. If we think about verbs that have been created in the past 20 years (e.g. “to email”, “to text”, or “to google”) all of them follow the regular verb conjugation patterns of adding an ‘-ed’ to form the past tense (e.g. “I emailed you yesterday” or “I just googled it”). On the other hand, the oldest, most irregular, most frequent verbs (like “to give” and “to be”) have been around in our language since a time when conjugation rules were different. All the old verbs that were birthed alongside “to give” and “to be” have since slipped into a bottomless pit of irrelevance, and new, more regular verbs replaced them to define the new concepts we discovered as our world unfolded before us.1

Show Me the Data

To understand the numerical relationship between verb frequency-of-usage and verb irregularity, we need to measure the two quantities from data.

To measure verb frequency-of-usage, I use a database of movie subtitles in Brazilian Portuguese, built by Tang, K 2012.2

To measure verb irregularity, I scrape data on verb-conjugations and their irregularity from a popular Portuguese verb-conjugation website. I then measure verb irregularity as “what fraction of this verb’s conjugations are irregular”3.

Including these measurements in our table from above, we get the following frequencies and irregularities, noted in the bottom two rows:

| regular rules | andar (to walk) | chegar (to arrive) | dar (to give) | ser (to be) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person present | -o | eu ando (I walk) | eu chego (I arrive) | eu dou (I give) | eu sou (I am) |

| 3rd person present | -a | ela anda (she walks) | ela chega (she arrives) | ela dá (she gives) | ela é (she is) |

| 1st person plural present | -amos | nós andamos (we walk) | nós chegamos (we arrive) | nós damos (we give) | nós somos (we are) |

| 3rd person plural present | -am | eles andam (I walk) | eles chegam (they arrive) | eles dão (they give) | eles são (they are) |

| frequency | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.154 | |

| irregularity4 | 0 | 0 | 0.75 | 1.0 |

As mentioned earlier, this table increases from left to right by both frequency-of-usage and irregularity; and now we have the numbers to show it! With this intuition, let’s take a look at this phenomenon for the top 50 most common verbs:

It’s nice when the numbers match the intuition! There’s a correlation between verb irregularity and frequency-of-usage; hover over the plot to see the individual verbs ;)

Zipf up your Boots

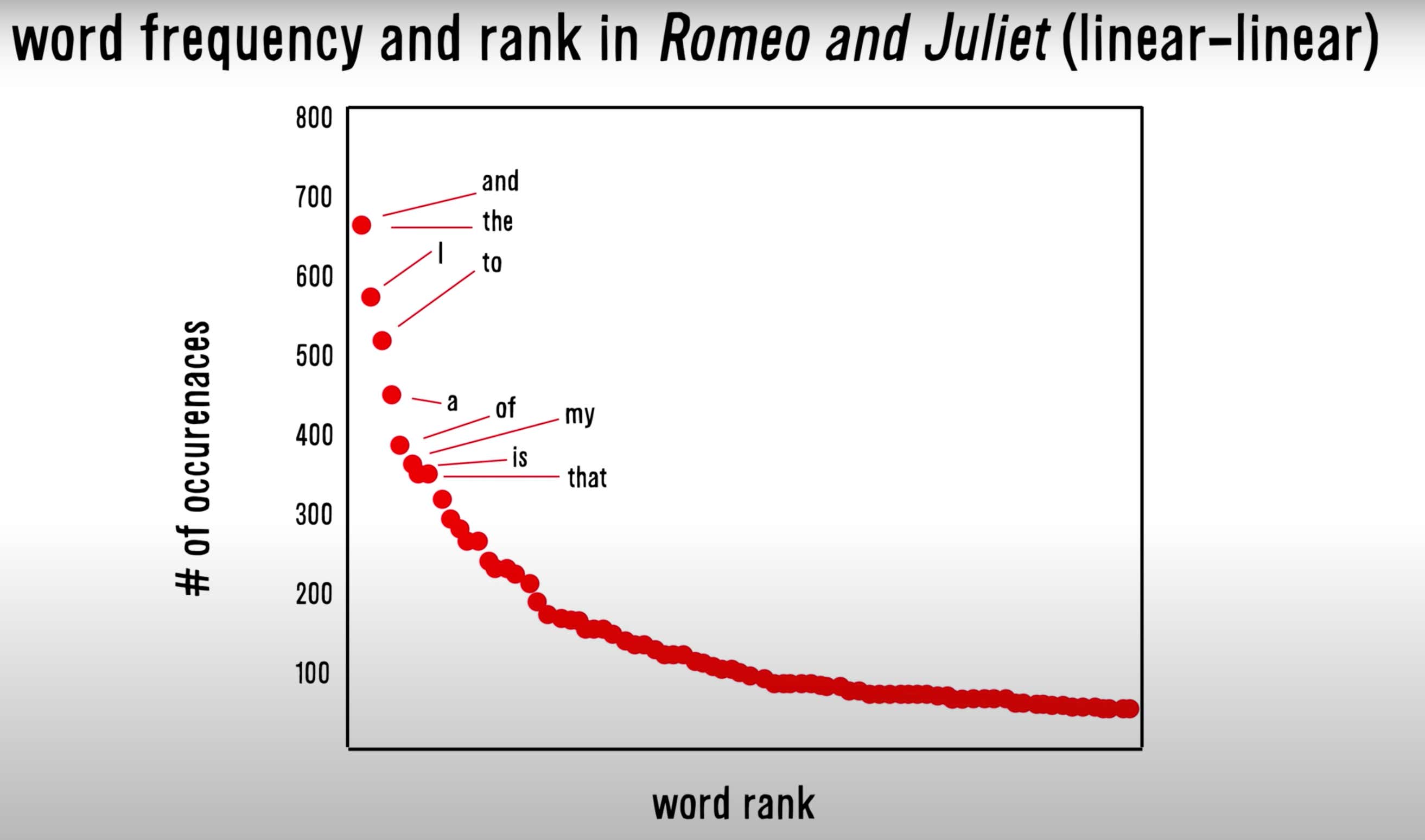

Thinking about verb frequency-of-usage gets me further thinking about Zipf’s Law. Zipf’s Law, as applied to word frequency in language, states that (from Wikipedia):

“…given some corpus of natural language utterances, the frequency of any word is inversely proportional to its rank in the frequency table. Thus the most frequent word will occur approximately twice as often as the second most frequent word, three times as often as the third most frequent word, etc…”

Power laws are found in all sorts of emergent systems; not just in language. Could it be that verb frequency-of-usage also follows power law like behavior? Let’s have a look:

Zipfy-doo-da, can somebody say “jackpot”? This looks positively Zipfian, even promisingly powerful.

Final Thoughts

It can be a bit frustrating for language-learners that the most common verbs have the most irregular conjugations; myself included. However, this phenomenon is also a window into the beauty of language. Insofar as a language is a naturally evolving system, it adheres to certain self-organizing behaviors that other emergent systems do. Languages are living, breathing systems that evolve over millenia, and the verbs “to go” and “to be” have been a part of them since the time of my most distant linguistic ancestors. As such, I don’t mind giving these verbs the most attention; on the contrary, it feels even honorable and respectful to do so.

Liked what you read? Feel free to reach out on , , , , and .

There exist many complex processes involved in the creation, regularization, and irregularization of verbs. Famous linguist Steven Pinker gives two examples of such processes from as recent as the past 100 years, with the verbs “to sneak” and “to dive”. In the past 100 years, the past tense of the verb “to sneak” recently irregularized from “I sneaked” to “I snuck”, while the past tense of “to dive” recently irregularized from “I dived” to “I dove”. Verbs can be created, become regular, and become irregular (for example, check out the complex suppletive etymology of the English verb “to be”). Verb evolution and irregularity is until this day a contentious linguistics research topic, and the reasoning provided in this post is simplified for the sake of clarity and brevity. For a deeper understanding, consider the book “Words and Rules”, by Pinker, which explains more about where regular and irregular verbs come from. ↩︎

There’s a considerable difference between written language and spoken language, and any linguistics study of natural language data is better off using spoken language. This is because written language is premeditated, edited, and curated, while only spoken language is truly spontaneous and generative. The only problem is that spoken language isn’t usually recorded (unless if you have an Alexa in your home). So, movie subtitle data is a pretty decent approximation at spoken language, as Dr. Tang’s paper about the movie-subtitle dataset demonstrates.

As a curious side-note on this point, everything that we know about Latin actually comes from Classical Latin, or Literary Latin, i.e. the Latin that was written down. It’s often said that Latin is the parent of all modern Romance Languages. However, that’s not entirely true. All of today’s modern romance languages actually descend from the Latin of the commoners, Vulgar Latin; not from Classical Latin. ↩︎As an example, see the conjugations for the verb “ir” (to go); irregular conjugations are denoted as such with an asterisk “*"). ↩︎

This is an abridged conjugation table. It ignores all the other verb tenses, e.g. future, past participle, subjunctive, etc. The irregularity is measured only on the abridged table, to be as clearly demonstrative as possible. ↩︎