Refactoring For Data Scientists: A Beginner's Guide

“The only way to go fast is to go well.” - Martin Fowler

A Tale of Two Programmers

Joe and Jane are university students taking the same “Introduction to Programming” course, and they’ve just been given the final project: build a Tetris clone! Nervous that they will complete such a big project in time, they both go home and get started right away.

Joe starts writing code, and he quickly completes the code for the game initiation, and even implements the “L” piece! Things are going well, but as he goes to implement more of the Tetris pieces, he finds that each one takes longer and longer to write. Every time he tries to write the code for a new Tetris piece, he finds that it’s harder and harder to fit it in to the already-existing code. What’s more, every time he adds new code, bugs pop up in unexpected places that take increasingly long to fix, to the point that he wishes he could start over. With just three days until the deadline, he goes to his friend Jane for help.

Jane, also anxious about the big project, got started immediately by writing the code for the game initiation and the “L” piece, just like Joe. Unlike Joe, however, she quickly realized that, before writing the code for the other pieces, she should generalize the “L” piece to subclass a more general “Piece” class. With this rhythm of writing, then reflecting, then writing, then reflecting, she works; and though she’s slow to start, she finds that as time goes on, the code gets easier and easier to write. Things build nicely off each other, and she is due to finish her project with a few days to spare!

Luckily, Jane is already done with her project by the time that Joe comes to her for help; she’s able to help him untangle some of his code and finish everything, just in time for the deadline, and they programmed happily ever after 🌈

Slow and Steady Wins the Race

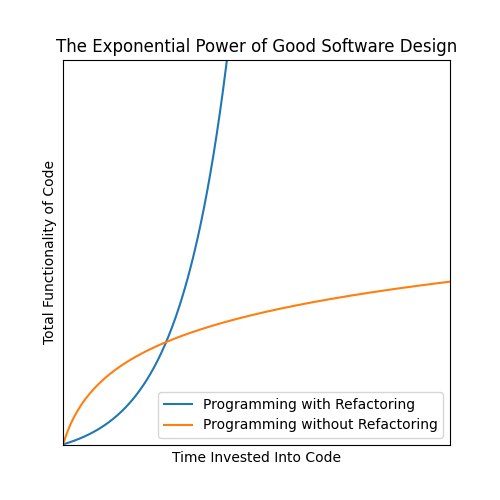

What’s the difference between Joe and Jane? Why does Joe experience logarithmic returns on time invested, while Jane experiences exponential returns on time invested?

The answer is that, while Joe only ever adds new features to his code, Jane, before every time she wants to add a new feature, takes a moment to improve the design of her code to be more amenable to the introduction of the new feature. While Joe was faster at the beginning, it didn’t take long for him to get overtaken by Jane.

This process of improving the design of code such that it’s more amenable to the addition of new features, while retaining the code’s observable behavior, is called “Refactoring”, and learning how to refactor can 10x any software developer’s productivity.

But enough story-time; what does this mean for data scientists? After all, we’re not software developers, right? Right??

Here’s My Model, Thank You Very Much

Not unlike Joe, a day in the life of a data scientist involves equations and models whizzing through our heads, pouring from our mathematical minds into our keyboards, leaving trails of messy code and messier whiteboards scattered in our wakes. But programming is a means to an end for us; there’s no need to write code cleanly! The job will be short anyway; we just need to run one experiment, write just one query!

Once we have gotten our analysis or our model just right, we hand over our code to the engineers to scale it and productionize it, say “voila”, and wash our hands clean. We whistle our way on to the next experiment, with full confidence that the engineers will take care of everything.

Things rarely work so smoothly, though. If the engineers can even read our poorly written code (how could they read it, with variables like df_original, df_final, and df_final_2), they quickly find out that the code doesn’t scale, that they don’t know how to conform the code to existing architecture, or that it’s so brittle that it breaks when they so much as touch it. Sometimes, if there’s enough value in the project, the data scientist gets brought back in, and more time is budgeted; other times, however, the project just fizzles and dies.

We might think that we’re not software developers, but insofar as we write code, we are in fact software developers! And with this, we must be empathetic to our engineering compatriots, so that we can all deliver products together in a timely and forward-compatible manner. We must write clean, well designed, future-proof code. And to do so, we must refactor.

But how?

How to Refactor

In his book “Refactoring”, Martin Fowler describes the two hats that all software developers must alternatingly wear: the “add features” hat, and the “refactor” hat [1].

When we are wearing the “add features” hat, we are writing new code; and when we are wearing the “refactoring” hat, we are seeking bad code (e.g. duplicated code, nested loops or conditionals, mysterious names) and snuffing it out.

So, how can you know what bad code looks like? And more importantly, how can you know how to refactor it when you find it? In these next three sections, we’ll start with a piece of data science code that compares the performance of two models; then, we’ll sequentially improve that code, one refactoring at a time:

1. Fixing Duplicated Code by Pulling Up a Function

Bad Code Smell: Duplicated Code

Refactoring Motif: Pull Up Function

Imagine you are trying to compare the performance of Adaboost versus RandomForest on the famous Kaggle Titanic Competition:

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier, AdaBoostClassifier

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

def load_df():

df = pd.read_csv('../data/titanic_dataset.csv')

df["is_male"] = df["Sex"] == "male"

return df

def evaluate_adaboost_model(data):

X = data[["is_male", "SibSp", "Pclass", "Fare"]]

y = data['Survived']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2)

model = AdaBoostClassifier()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

accuracy = model.score(X_test, y_test)

return accuracy

def evaluate_random_forest_model(data):

X = data[["is_male", "SibSp", "Pclass", "Fare"]]

y = data['Survived']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2)

model = RandomForestClassifier()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

accuracy = model.score(X_test, y_test)

return accuracy

df = load_df()

accuracy_adaboost = evaluate_adaboost_model(df)

print(f"AdaBoost Accuracy: {accuracy_adaboost:.3f}")

accuracy_random_forest = evaluate_random_forest_model(df)

print(f"Random Forest Accuracy: {accuracy_random_forest:.3f}")

And now, you want to add an additional comparison for XGBoost before handing it off to some engineers to run it on a much larger dataset. But first, you smell something is amiss… are you really going to create a new function, evaluate_xgboost_model()? evaluate_adaboost_model() and evaluate_random_forest_model() already appear to have a lot of repeated code that you’d have to copy and paste.

Well, if you find yourself needing to copy and paste code, it’s usually a hint to refactor. To fix this case of duplicated code, we’ll use the “pull up function” refactoring, in which we extract a generalized version of two nearly identical functions*. More specifically, we’ll pull up a function evaluate_model(), which will take in the model of interest as an argument, thus deprecating evaluate_adaboost_model() and evaluate_random_forest_model():

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier, AdaBoostClassifier

def load_df():

df = pd.read_csv('../data/titanic_dataset.csv')

df["is_male"] = df["Sex"] == "male"

return df

#### PULLED UP METHOD ####

def evaluate_model(data, model_constructor):

X = data[["is_male", "SibSp", "Pclass", "Fare"]]

y = data['Survived']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2)

model = model_constructor()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

accuracy = model.score(X_test, y_test)

return accuracy

df = load_df()

accuracy_adaboost = evaluate_model(df, AdaBoostClassifier)

print(f"AdaBoost Accuracy: {accuracy_adaboost:.3f}")

accuracy_random_forest = evaluate_model(df, RandomForestClassifier)

print(f"Random Forest Accuracy: {accuracy_random_forest:.3f}")

Instead of immediately putting on the “add features” hat, we took a moment, and put on the “refactor hat”. Without changing the observable behavior of the code, we managed to improve its internal design in such a way that not only did our code get shorter, but adding an extra model-evaluation for XGBoost (and any other model) is now trivial:

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

accuracy_xgboost = evaluate_model(df, XGBClassifier)

print(f"XGBoost Accuracy: {accuracy_xgboost:.3f}")

2. Fixing a Mysterious Name by Renaming a Variable

Bad Code Smell: Mysterious Name

Refactoring Motif: Rename Variable

Now, let’s say you got good results (yay!), so you show it to your colleague, who immediately interrupts you by saying “What’s actually in df though?”.

Often, renaming a variable has the highest ratio of reward-to-effort of any refactoring motif; with a little bit of thought and just a few keystrokes, you can preemptively answer questions about the data that’s getting passed around your code. In this case, it should be easy to come up with a clear name that communicates precisely what’s inside of our dataframe; doing so will not only answer your colleague’s question, but it will preempt any other such questions:

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier, AdaBoostClassifier

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

#### RENAMED FUNCTION ####

def load_titanic_passengers_df():

titanic_passengers_df = pd.read_csv('../data/titanic_dataset.csv')

titanic_passengers_df["is_male"] = titanic_passengers_df["Sex"] == "male"

return titanic_passengers_df

def evaluate_model(data, model_constructor):

X = data[["is_male", "SibSp", "Pclass", "Fare"]]

y = data['Survived']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2)

model = model_constructor()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

accuracy = model.score(X_test, y_test)

return accuracy

#### RENAMED VARIABLE ####

titanic_passengers_df = load_df()

accuracy_adaboost = evaluate_model(titanic_passengers_df, AdaBoostClassifier)

print(f"AdaBoost Accuracy: {accuracy_adaboost:.3f}")

accuracy_random_forest = evaluate_model(titanic_passengers_df, RandomForestClassifier)

print(f"Random Forest Accuracy: {accuracy_random_forest:.3f}")

accuracy_xgboost = evaluate_model(df, XGBClassifier)

print(f"XGBoost Accuracy: {accuracy_xgboost:.3f}")

After renaming df to titanic_passengers_df and load_df() to load_titanic_passengers_df(), there’s no doubt at all – every row in the newly named titanic_passengers_df represents a distinct passenger from the Titanic. Nice!

3. Fix Magic Values by Extracting Variables

Bad Code Smell: Magic Values

Refactoring Motif: Extract Variable

So you’ve discussed it to your colleagues, and they all agree: you’ve got some great results! Now, it’s time to share it with the engineers in your team to scale it to more data; the only problem is that the engineers are not so familiar with data science and machine learning, and they immediately ask “what are these string values at the top of the evaluate_model function?”.

Instead of saying “they’re features and a target for our model, silly engineer!”, we can answer all engineers’ such questions permanently by extracting the requisite variables from our code:

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier, AdaBoostClassifier

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

#### EXTRACTED VARIABLES ####

MODEL_FEATURES = ["is_male", "SibSp", "Pclass", "Fare"]

MODEL_TARGET = "Survived"

TRAIN_TEST_SPLIT_FRACTION = 0.2

def load_titanic_passengers_df():

titanic_passengers_df = pd.read_csv('../data/titanic_dataset.csv')

titanic_passengers_df["is_male"] = titanic_passengers_df["Sex"] == "male"

return titanic_passengers_df

def evaluate_model(data, model_constructor):

X = data[MODEL_FEATURES]

y = data[MODEL_TARGET]

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=TRAIN_TEST_SPLIT_FRACTION)

model = model_constructor()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

accuracy = model.score(X_test, y_test)

return accuracy

titanic_passengers_df = load_df()

accuracy_adaboost = evaluate_model(titanic_passengers_df, AdaBoostClassifier)

print(f"AdaBoost Accuracy: {accuracy_adaboost:.3f}")

accuracy_random_forest = evaluate_model(titanic_passengers_df, RandomForestClassifier)

print(f"Random Forest Accuracy: {accuracy_random_forest:.3f}")

accuracy_xgboost = evaluate_model(df, XGBClassifier)

print(f"XGBoost Accuracy: {accuracy_xgboost:.3f}")

With the MODEL_FEATURES and MODEL_TARGET variables extracted, we significantly decrease ambiguity for future readers (and we extracted the TRAIN_TEST_SPLIT_FRACTION in case of future questions regarding that as well).

In summary, we:

- Fixed duplicated code by pulling up the

evaluate_model()function; - Fixed the mysterious

dfname by renaming it totitanic_passengers_df; and - Fixed the magic values in our code by extracting the variables

MODEL_FEATURES,MODEL_TARGET, andTRAIN_TEST_SPLIT_FRACTION.

Adding that extra evaluation for XGBoost was not only easier, but our code has become more readable to all audiences who are likely to interact with it.

There’s still plenty more refactoring that can be done to this code, but for now, it’s enough. Once it’s time to add the next piece of new functionality to the code, then the next most important refactoring will reveal itself.

Conclusion

Learning to refactor is an integral step on any software developer’s journey. And insofar as we as data scientists write code, we too are software developers; and with that, learning to refactor is an integral step on our journeys too. For a deeper dive into a practiced methodology for refactoring (and many more refactoring motifs than what’s mentioned in this article), I recommend the book “Refactoring” by Martin Fowler [1].

At the beginning of this post, we saw Joe lamenting to himself that “every time he adds new code, bugs pop up in unexpected places that take increasingly long to fix, to the point that he wishes he could start over”. And this raises a curious question – when do you know whether to start over, or to refactor? Is starting over ever the right decision?

This is always a tough question, and it rarely has a clear-cut answer. In writing software, as in nurturing human relationships, healing and rebuilding is usually more difficult than starting over – but it is also usually more robust and is almost always far more rewarding. Refactoring enables us to discover higher levels of internal design in the things we have already created, rendering us both more respectful of the past and more robust to the future.

References

[1] Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code, by Martin Fowler (with Kent Beck)

* Normally, the refactoring is not “pull-up function”, but rather “pull-up method”, in which one pulls up two nearly identical methods from two child classes into one common method in the parent class. This post discusses the analogous “pull-up function” refactoring for the sake of simplicity.

Liked what you read? Feel free to reach out on , , , , and .